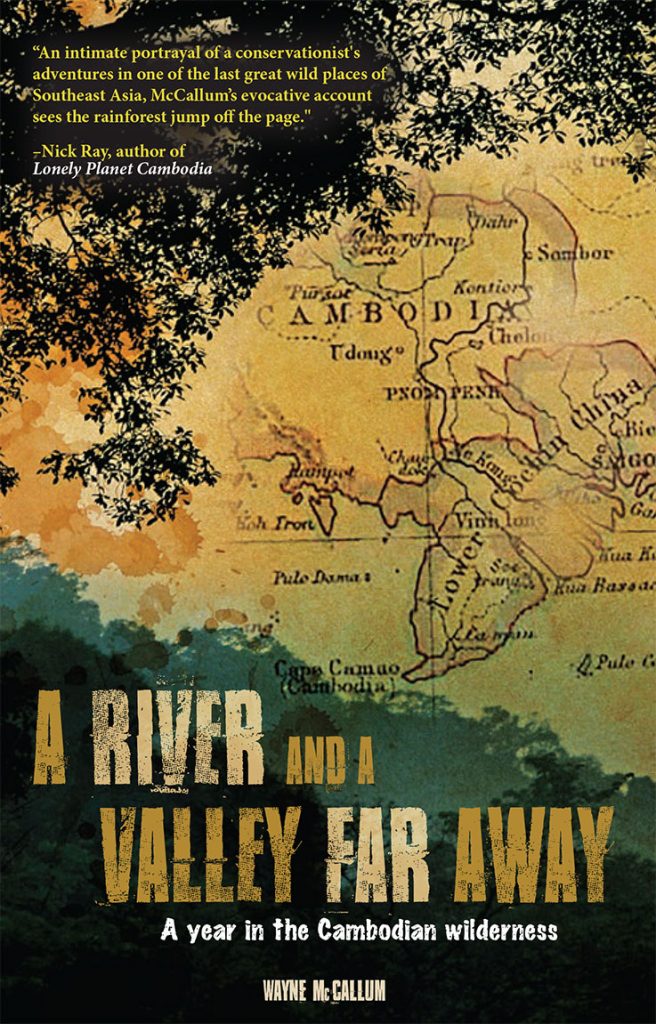

“An intimate portrayal of a conservationist’s adventures in one of the last great wild places of Southeast Asia, McCallum’s evocative account sees the rainforest jump off the page.”

—Nick Ray, author of Lonely Planet Cambodia

“McCallum’s affectionate recounting of his volunteer year, based in the rainforest world of the Elephant Hills, is part memoir, part record of frontier Cambodia—from the vibrancy of village life, to the challenge of protecting the forests and creatures of this unique wilderness region.”

— Robert Carmichael, author of When Clouds Fell from the Sky

With the humour of Bill Bryson, the soul of George Orwell and the spirit of Indiana Jones, A River and A Valley Far Away is a tale of what befalls a volunteer from small-town New Zealand when he is assigned to a remote corner of Cambodia. Humorous, sombre and insightful, the story provides a captivating account of a time and a world fast disappearing.

-

- Two of the ‘Septuagenarian Rice Reapers of 2004’ with their container of rice wine close by (Chapter 24).

-

- Chumnoab village, third night on the Hornbill Trail. During the evening we enjoyed some ‘movie night’ entertainment at the village chief’s house (Chapter 29).

-

- Ghosts from the past: the backpackers kidnapped from the Phnom Penh to Sihanoukville train by the Khmer Rouge (1994). The three men were eventually executed by their captors (Chapter 23).

-

- Sunset over the Prek Kampong Som from my riverside deck. Watching the sun set was a dry season ritual.

-

- Cardamom Mountains: Phnom Krapeu, our destination on the first day on the Hornbill Trail (Chapter 28).

Prologue to A River and A Valley Far Away

The Underpants of Mass Destruction: night comes quickly in a tropical rainforest, especially during the wet season, where the canopy filters further any light able to penetrate the monsoon gloom. So this evening, yet again, we had barely paused to make camp before finding ourselves stumbling in the twilight, seeking wood for our fire and spots for our hammocks.

The day had been a long one. Four kilometres of trekking may sound straightforward, but across gullies and hills, through forest and scrub, it had been a fatiguing distance. So it felt good to rest at the evening’s end—to swing in the comfort of a hammock while listening to raindrops on the tarpaulin overhead.

Later, past midnight, I am still awake, staring at the plastic sheet above, while listening to my colleagues, local villagers all of them, snoring and talking in their sleep. A number of them are ex-Khmer Rouge, and once fought in the rainforest where we now rest, keeping the government troops at bay for a decade or more. Back in Phnom Penh some say that they were never defeated, but simply chose to rest. They make interesting bedfellows.

Annoyingly tonight, in spite of my tiredness, I find it difficult to sleep, waking in fits and starts. Below, beneath my clothes, my thinning frame is not coping well with this latest rainforest escapade either. At breakfast, my body reached rice saturation and, unable to eat a further mouthful, I declared myself on ‘rice strike’. Given its prominence in every Khmer meal—sometimes it is the meal—my resolution means that I will eat little more on this trip.

Compounding this, a hearty bout of diarrhoea heralded itself earlier in the day, sending me scurrying for the cover of some nearby bushes, to the unsympathetic laughter of my forest colleagues. My body is now like the economy of an indebted nation—nothing is going in, while what remains is swiftly disappearing, my energy reserves collapsing—bankruptcy looming. But there are no bailouts here, only pride and necessity to keep me going. I drift in and out of consciousness, my bowels and stomach rumbling like a spiteful Vesuvius.

I must have drifted off, but I am awake now and my posterior is signalling the need to exit to the nearest bush—fast. I struggle to disentangle myself from my hammock, ensnaring myself in my mosquito net, before tripping over a pair of boots sprawled across the jungle floor. Staggering and dazed, I stumble into the nearby forest, stubbing my toe on a tree root. “Shit”. The word is prophetic. I am too late. An accident ensues. “Damn”. I revert to clear-up mode, dealing with the worst of the damage, trying to make things more habitable. I bend down and make to remove my soiled underpants.

My trousers are around my ankles, the underpants of mass destruction in my hand, when I hear something approaching, a new sound in the jungle night. It is growing nearer, closer by the second: the noise disconcertingly loud. In my head I make a hurried calculation: ‘big buzz, big bug!’ Having seen the size of the insects in this forest, including beetles the size of matchboxes, I expect that the source of this noise is hardly something to be trifled with sans pants.

A defensive manoeuvre is required and—holding tightly—I wave the only item close at hand, my underpants, towards the intruding sound. Thankfully, it seems even large jungle insects find the garment offensive and, after a couple of hasty swipes, the buzz fades into the night. I let out a long sigh: the winged creature has made a life decision to pursue options in a less hostile part of the jungle. I am grateful.

Normal reception resumes. Cicadas hum, while from our fly camp I can hear the sound of my snoring colleagues. Pulling up my pants, I return to my hammock and settle into my cold blanket, hoping for a few hours of undisturbed sleep (in the jungle, it pays to be an optimist). Behind me, my underpants lie alone on the forest floor, pondering, if underpants can ponder, what to make of this latest turn of events. Turning in my bed I do not give them another thought: after all, there is only so much you can handle at 2:30 in the morning.